In the early twentieth century, Fort Saskatchewan was a town on the move, brimming with possibilities and potential. The Canadian Northern Railway’s (CNoR) transcontinental line arrived in town in 1905 providing farmers with better access to markets near and far, while putting the town on a direct line for settlers moving westward. The CNoR’s president, Sir William MacKenzie, even made a rosy prediction that Fort Saskatchewan’s population of just under 1000, in 1911, would explode to 10,000 people within five years.[1] Eager to fulfill MacKenzie’s prognostication, Fort Saskatchewan’s Board of Trade set out to attract more settlers to their bustling little burg.

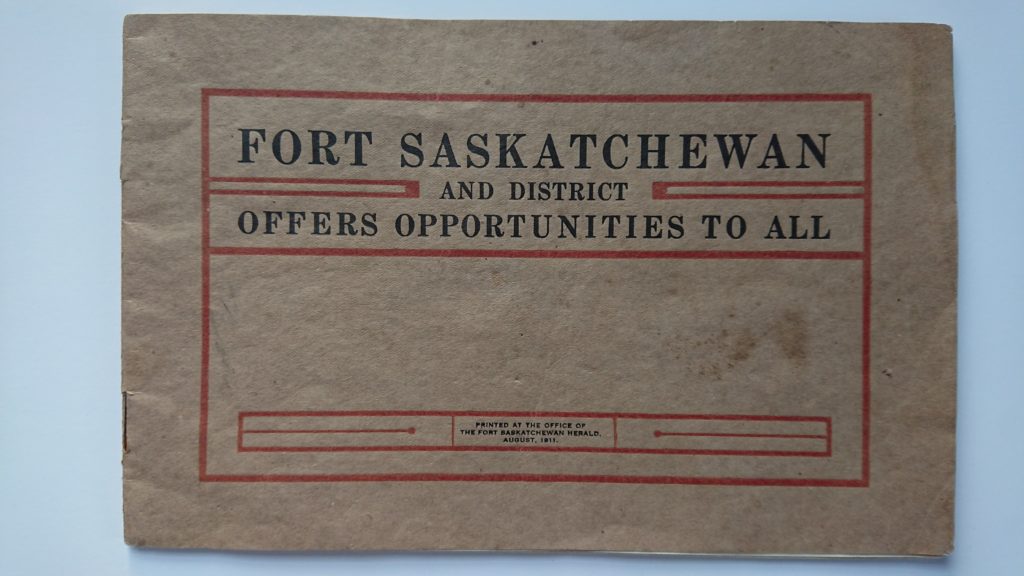

In 1911, they published a pamphlet titled “Fort Saskatchewan and District Offers Opportunities to All” to promote the town. The pamphlet featured photographs of attractive, well-built farmhouses to signify the wealth of the land and highlighted a Main Street (102 Street) buzzing with activity to attract potential entrepreneurs. The town’s boosters had much to be prideful over, as Fort Saskatchewan had been the first town between Winnipeg and Edmonton on the CNoR line with sidewalks, electricity, telephone service, and a modern brick schoolhouse. Fort Saskatchewan had also emerged as a market town and industry was growing. Construction of a hydroelectric dam and power plant on the Sturgeon River four miles away (which would later fail after the dam collapsed) promised enough potential surplus power for an iron foundry, creamery, tile works, pulp and lumber mills, and a cold storage facility. The Board was also dizzy with excitement over the possibility that the CNoR might make Fort Saskatchewan a divisional point and build their roundhouse and shops in town.[2] The town had much to offer prospective settlers and the potential for growth appeared endless.

As the Board of Trade looked to attract new settlers to Fort Saskatchewan, their promotional pamphlet coincided with efforts by the Canadian government and other municipalities across Western Canada to promote immigration and settlement in the West. Known as “The Last Best West” campaign, Canada’s immigration policy in the early twentieth century prioritized white farmers from Britain and the United States. The initial “Laurier Boom” brought two million new settlers to the country, primarily from Britain, followed by the U.S., Austro-Hungary, and Ukraine. Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier’s first minister of the interior, Clifford Sifton (1896 – 1905), opened Canada’s immigration preferences to include Eastern Europeans, but directed government agents to discourage immigration of Jews, Asians, Italians, African Americans, and urban Englishman.[3]

Edmonton’s Frank Oliver replaced Sifton in 1905 and continued to promote immigration efforts to farmers from Britain and the U.S. Oliver, however, was shocked to find that Canadian immigration advertisements were not only targeting white Americans but also appeared in newspapers in all-Black towns like Boley, Oklahoma.[4] A number of Black Americans in Oklahoma had been prosperous landowners and merchants until Oklahoma achieved statehood in 1907, and a tide of white supremacist legislation stripped many Black people of their property and rights. The combination of racial violence at home and Oliver’s advertisements for 160 acres of free farmland, with promises of wealth and prosperity, in Western Canada, led approximately 1000 Black settlers to seek refuge in Alberta between 1908 and 1911.

Fort Saskatchewan’s own promotional pamphlet, while “offering opportunities for all,” largely mirrored Canada’s immigration policy. Its language aimed to appeal to white farmers in either Britain or America. The pamphlet describes that a “pleasing feature” of the settlers in and around Fort Saskatchewan is that they are “exclusively English-speaking… composed of Canadians, English, Scotch, Irish and Americans.”[5] While noting that the French settlement across the river is populated by the “very best type of French Canadian,” it also ignored the presence of a large number of German-speaking settlers in the area, Ukrainians, Indigenous and Métis peoples, and the few Chinese settlers in town (Mah Sing and his nephews owned several parcels of land, a laundromat, and a restaurant downtown between 1911 and the 1940s).

Neither the pamphlet nor Canada’s 1906 immigration act explicitly mentioned race, but in 1911, Fort Saskatchewan’s Board of Trade joined Edmonton and the boards of trade in Strathcona, Calgary, and Morinville in petitioning the Laurier government to ban Black immigrants from entering Canada.[6] Although some Albertans defended the rights of Black immigrants, others, like the members of the Imperial Order of the Daughters of the Empire in Edmonton, wrote angry letters to Oliver arguing that the “rapid influx of Negro settlers” would bring property values down and discourage whites from settling in the vicinity of Black farmers.[7] The petition rightfully acknowledged that its writers could not discern whether Black settlers would make good farmers or citizens, but instead claimed that a continuation of Black immigration to Alberta would lead to “bitter race hatred” and lawlessness.[8]

Oliver responded to the petition by drafting an Order in Council that “banned any immigrants of the Negro race” from entering Canada for one year.[9] Laurier approved the order but it never became law, as he supposedly did not want to upset ongoing trade negotiations with the United States. With his legislative ban stalled, Oliver instead sent agents to Oklahoma to discourage Black immigration. They claimed Canada was a barren, arctic wasteland, while at the same time worked to dispel rumours of Canada’s harsh, cold climate to potential white settlers.[10] Black immigrants were also scrutinized at the border by immigration agents over their physical health and finances. Oliver’s policies eventually worked and after 1911 Black immigration to Canada declined.

The Fort Saskatchewan Board of Trade’s endorsement of the petition to ban Black immigration to Alberta succeeded in limiting the settlers they did not want in the district and made it clear that, despite their pamphlet’s claim, opportunities were not actually “available to all.” The promotional pamphlet also largely failed to attract the settlers they did want. The Great War would follow in a few short years, all but ending British and European immigration to the Canadian prairies until after the war. The Fort’s population remained around 1000 people until the arrival of Sherritt-Gordon and other industries in the 1950s. It would take 100 years for the town to finally reach Sir William MacKenzie’s prediction.

Today, outside of the petition to ban Black immigration, Fort Saskatchewan’s connection to the early twentieth-century wave of Black migration to Alberta is largely unknown. The Fort is 150 km south of Amber Valley, in its heyday the largest Black settlement in Alberta, and the Fort was an important supply centre for settlers moving north in the early 1900s. Did any of Amber Valley’s pioneers stop in Fort Saskatchewan for supplies? Possibly, although St. Albert or Morinville may have been more likely depending on their route north from Edmonton. Did any early Black settlers try to make Fort Saskatchewan and District their home? Our records are largely silent on the topic but further exploration of federal census records, provincial heritage resources, and the Fort Heritage Precinct archives may hopefully someday shed some light.

[1] Fort Saskatchewan Board of Trade, Fort Saskatchewan and District Offers Opportunities to All (Fort Saskatchewan Herald, 1911), 14.

[2] Ibid., 17.

[3] “Selling the Prairie Good Life,” Canada’s History, Accessed February 2, 2021, https://www.canadashistory.ca/explore/settlement-immigration/selling-the-prairie-good-life

[4] Dr. Russell Cobb, “The Last Black West: Oklahoma Freedmen Seek Refuge in Alberta, Part 1,” Edmonton City as Museum, Accessed February 15, 2021, https://citymuseumedmonton.ca/2021/02/09/the-last-black-west-oklahoma-freedmen-seek-refuge-in-alberta-part-1/?fbclid=IwAR3tF1FrUltG5j4TLpwDZdmlgiH1uNa8N6NweGWjPfpN64XgWJH5SqoWOek

[5] Board of Trade, 16.

[6] “Black Settlers Come to Alberta,” Collections Canada, Accessed February 11, 2021, https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/eppp-archive/100/200/301/ic/can_digital_collections/pasttopresent/opportunity/black_settlers.html

[7] Dr. Russell Cobb, “The Last Black West: Oklahoma Freedmen Seek Refuge in Alberta, Part 2,” Edmonton City as Museum, Accessed February 15, 2021, https://citymuseumedmonton.ca/2021/02/09/the-last-black-west-oklahoma-freedmen-seek-refuge-in-alberta-part-2/?fbclid=IwAR3VBQlMLXD1vAivlel9NlSHVSdB3QCe_l9C9oe6h5nrWj4urrj_ptdkO24

[8] Edmonton Capital, “The Petition,” April 25, 1911, Accessed February 15, 2021, https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/eppp-archive/100/200/301/ic/can_digital_collections/pasttopresent/opportunity/petition.html

[9] Alan Rowe, “African American Immigration to Alberta,” RETROactive, Accessed February 15, 2021, https://albertashistoricplaces.com/2015/02/12/african-american-immigration-to-alberta/

[10] Ibid.