On 11 July, we installed the new mini-exhibit, Photographic Memory, in the Fort Saskatchewan City Hall Foyer. The exhibit displays ten vintage cameras from the Fort Heritage Precinct’s permanent collection and several historical photographs of Fort Saskatchewan on exhibit panels. The inspiration for the exhibit came about while attending the National Council on Public History Annual Conference earlier this year in Hartford, CT, where a session panelist presented a brief history of the Eastman Kodak Company and the camera as a “memory machine.” Eastman Kodak developed the first handheld box camera in 1888 and their most popular early 20th-century camera, the Brownie, arrived in 1901.

Kodak’s handheld box cameras democratized the art of photography. They were inexpensive, retailing initially for $1.00, and easy to use. C.B. Larrabee, writing in Printer’s Ink in the early twentieth century, remarked, “[the] big idea behind the selling of Eastman Kodaks is that every man can write the outline of his own history and that the outline will be a hundredfold more interesting if it is illustrated.” Kodak’s new handheld box cameras made it easier for anyone to become a visual historian for their family and community, capturing moments small and large for posterity.

“Kodak, as you go,” 1917 (Duke University Libraries Digital Collection).

The new developments in photography also coincided with the settlement of Fort Saskatchewan. When the Brownie arrived on store shelves in 1901, the Fort was a bustling village, Northwest Mounted Police (NWMP) division headquarters, and agricultural community. Although, much of Fort Saskatchewan’s early visual history comes to us from professional photographers like C.W. Mathers, Ernest Brown, and J. Bell, many amateur photographers were taking advantage of the new portable cameras available to them.

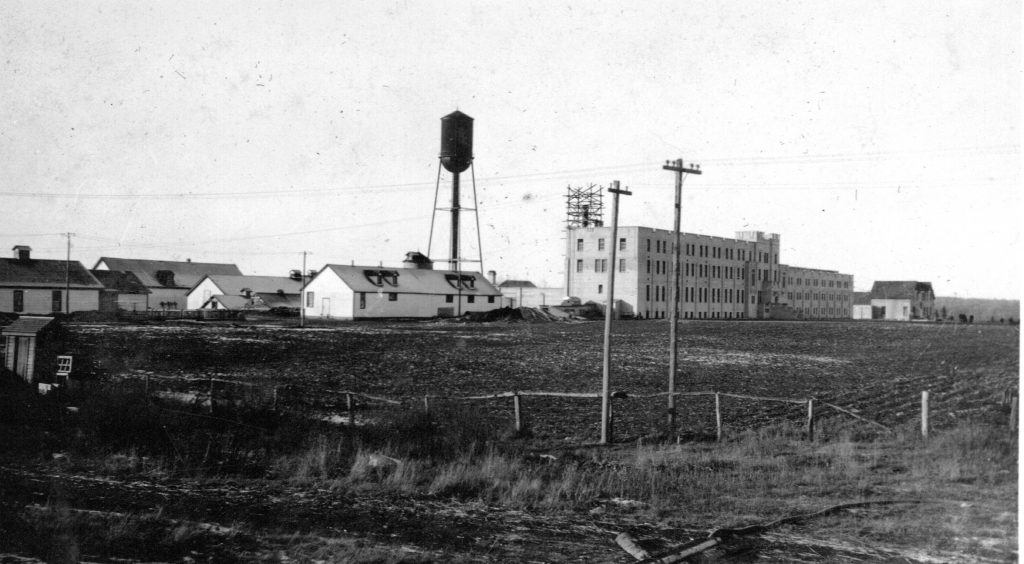

Thomas Sidney Umpleby is one example of amateur photographers who helped capture the early histories of booming prairie towns like Fort Saskatchewan. Possibly taking inspiration from Eastman Kodak’s “Kodak as you go” sales pitch, Umpleby, a dry goods salesman from Winnipeg, liked to carry his camera on business trips and snap the local scenery. Below is a photograph by Umpleby of the Fort Saskatchewan Gaol sometime between 1914 and 1918.

Fort Saskatchewan Provincial Gaol, circa 1914-1919. Photo by Thomas Sidney Umpleby.

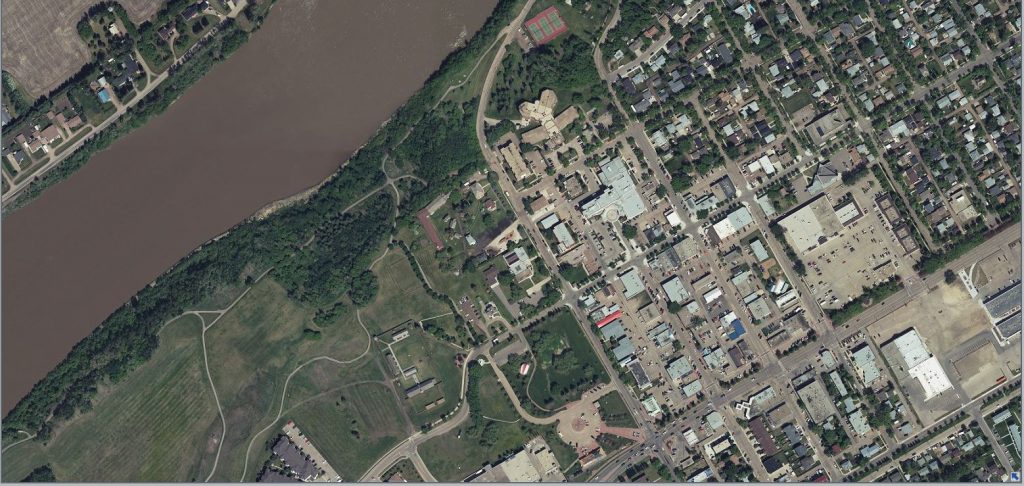

One of the main takeaways of the Photographic Memory exhibit is the important role photography plays in documenting community history. Historians frequently use the expression “the past is a foreign country,” a reminder to be careful about imposing present-day values on people or events in the past; but in the context of visual history, historical photographs can help make the foreign more familiar. In particular, historical photographs allow the viewer to see commonalities as well as differences between the past and present. If you examine the aerial photograph of Fort Saskatchewan from 1964 below, you will find the Provincial Gaol at the center of town occupying a large expanse of land. By comparison, the aerial photograph from 2017 shows the gaol buildings gone and replaced by the Fort Heritage Precinct’s replica NWMP Fort and historical village.

Downtown Fort Saskatchewan, circa 1964

Downtown Fort Saskatchewan, 2017 (http://mapping.fortsask.ca/Content/Server/Login.aspx?ReturnUrl=%2fmunisightES)

The differences in the photographs are obvious, but the similarities are striking. The historic site still sits atop the low banks of the North Saskatchewan River where thick strands of trees on the edge of the embankment continue to provide the city with a lush pastoral setting, even as it grows and urbanizes. Both the prison trails and the old trails that once led NWMP constables and early settlers down to the river ferry landing, and now used as recreation paths, are visible in both photographs. We also see downtown’s grid plan unchanged. In fact, the street grid has remained the same since the 1890s. These similarities are the threads that connect our community to its past. They provide a sense of place, a rootedness, but often go unseen or taken for granted at ground level.

Visual history illuminates the similarities between the past and the present, and going back to Larrabee’s idea of the camera as a “memory machine,” photography also helps us remember what has been lost over time. As our community’s built environment continues to change, it becomes difficult to recall what came before. Look at the series of photographs below: The four photographs show 101 Street between 101 Avenue and 100 Avenue from 1898 to 2019. Many residents may only be familiar with the current small walk-up apartment buildings, seniors housing, and Pioneer House that occupy the space now, but the photographs reveal layers of history on this site.

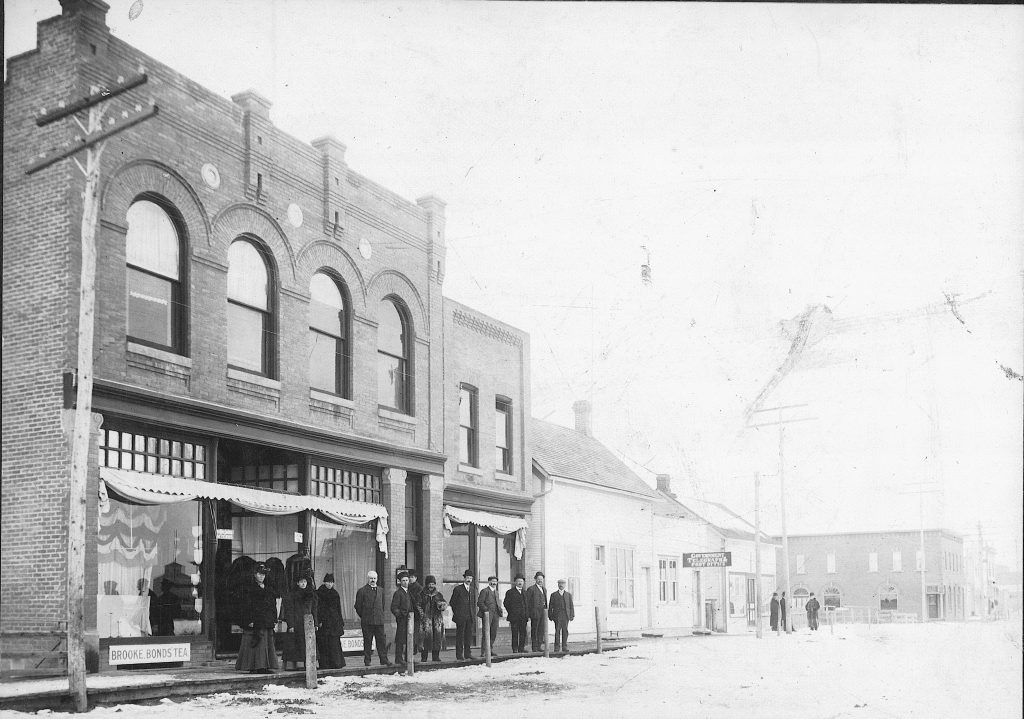

Shera & Co. store at 10111 101 Street, Fort Saskatchewan, 1898. Photo by C.W. Mathers.

J.W Shera’s wood frame store, located on the corner of 101 Ave and 101 Street in the first photograph (1898), became a larger and more impressive brick store at 10011 101 Street in 1903, which you can see in the second image taken sometime after 1911. Notice the Mansion Hotel located at the far right of the first two photographs. It is a Queen Anne style wood-frame building in the first photograph, but a brick-clad Edwardian structure in the second. The change occurred in 1911. Pinder Chiropractic now occupies the site.

You will also see G.T. Montgomery’s business and post office buildings at 10007 101 Street. The main building is the structure with two chimneys and two smaller buildings to its immediate right. Montgomery built those additions in 1898 to accommodate the post office. The buildings appear in the middle of the frame in the first photograph, but next to Shera’s store in the second and third photograph. The three buildings served as the post office under Montgomery until, 1902, when A.W.M. Campbell purchased the business. Campbell remained in Montgomery’s building until at least 1906 when a fire destroyed some of the block, although the fire spared the post office. It also served as one of Fort Saskatchewan’s first nursing homes, The Fort Saskatchewan Hospital, under a Miss Bredeson until 1927.

Shera & Co. store, circa 1911. Photographer unknown.

The third photograph from 1977, or 1978, shows the Shera (O’Brien) Block and Montgomery building at the end of their lifespan. The image reveals significant changes to the façade of both buildings. The bricked over store windows, addition on the northwest side, and television antenna on Shera’s old store indicate it was likely used as an apartment residence before it was torn down in 1978 to make way for the current apartment buildings. Before then, however, it had served the community for seventy-five years as a general store, butcher shop, furniture store, drug store, funeral home, and International Order of Odd Fellows Hall. The fourth photograph, taken August 2019, shows us the current landscape of 101 street. Shera’s and Montgomery’s buildings are now gone and replaced by the River Drive Apartment block and the T.W.E. Henry Seniors Residence (current road work on 101 street prevented me from getting the whole block in the frame for a fuller perspective, unfortunately).

O’Brien Block (Shera Block), circa 1978. Photographer unknown.

River Drive Apartments (10011 101 Street) and T.W.E Henry House Seniors Residence (10007 101 Street), 2019. Photo by Fort Heritage Precinct Curator, Kyle Bjornson.

Information about these buildings, the businesses they contained and their proprietors come from traditional primary sources and the only secondary source on the history of Fort Saskatchewan, Peter T. Ream’s Fort on the Saskatchewan. It is difficult, however, to visualize how the buildings, or streetscape, would have looked in each phase of their long lifespan without the photographs in the Fort Heritage Precinct archives. They not only make the history of our community “a hundredfold more interesting,” but they connect us to our shared past, which would otherwise be long forgotten.

This brings us to the final takeaway from the Photographic Memory exhibit: taking photographs has never been easier; many of us do it regularly on our mobile phones and tablets. However, photographs taken today, if shared at all, are usually only posted to online social media accounts, many with private audiences. How many photographs taken of Fort Saskatchewan today will find their way into the Fort Heritage Precinct’s archives in the future?

Although, many of the threads that connect us to our shared history will remain intact, even as we continue to grow and develop, how visible will they be to future residents without visual history to illuminate them?

– KB